The Harvest Of What Remains

Wendy Drexler

Many apples ago, I climbed a crabapple tree, scrambled up to pick

the round, bitter fruit. Bitter but beautiful, that hard lesson I taught

myself to keep my desire from consuming itself, like those overripe

drops that fall in the orchard, thick with bruise and blight, spreading

like split hems beneath the trees. From the harvest of what remains—

ginger golds, ambers, russets, crimsons—see how they make

a welcome mat of their dying. Then stand at the door to find out

if you will be let in or locked out, if this is to be your last supper

or splendor’s summit, your squander, your reprieve, or the pulp

of sorrow. Pick yourself up from wherever you have fallen

to the ground, look around for a branch to land on, an unlatched

screen door that might open. And what will you do then with all

the light you’ve consumed, spellbound with mouthfuls of wonder,

when love tumbles its frantic windfall into your arms?

“It’s about life, it’s about death, even if I wasn’t consciously thinking of those things.”

Interview by L. Valena

October 24, 2022

Can you please describe the prompt that you responded to?

I responded to a very striking photograph of rotting and bruised apples, pressed close together in a rectangular shape, which reminded me of a welcome mat, which was on the ground in front of a screen door. That's what I took with me into the first writing that I did.

Where did you go from there?

I like to begin by describing what I'm seeing, and hope that it will open up a metaphor, or lead me to some kind of insight about the image. Mark Doty does this so well, a poet I really admire. I wrote in two takes, then I workshopped my draft with my poetry group and changed it around a little bit more. The night before, I had been introduced to a poet named Shangyang Fang; his book is called Burying the Mountain. I really loved his poems, and he used a striking phrase: “Many apricots ago, when I was a child.” So the first words I wrote were “Many apples ago, when I was a child.” I stole his line because it was such a cool way to get into it. And then I wrote that “the apples make a welcome mat of their dying, thick with fruit and bruise, blight and scab, gaseous exhalations erupting and glorious golds, russet, tawny, amber, marigold, spice.” At that point I was looking up different colors for apples. I kept writing. Some of this language made it into my final version, and some didn't.

Tell me more about apples.

I was working with the idea that the apples were there, bruised, and yet they were some kind of offering. I was also influenced by the fact that the previous week or so I had gone apple picking with my granddaughter, daughter, and son-in-law. It always strikes me how many apples ripen and drop on the ground. I know they probably use some of these drops for cider, but I imagine that some of the fallen apples just rot. So I had that image in my mind, as well as an image of climbing a crabapple tree when I was a child to pick those little apples. They looked so luscious, but I discovered they were really bitter and hard. That’s what I was thinking when I wrote “many apples ago.”

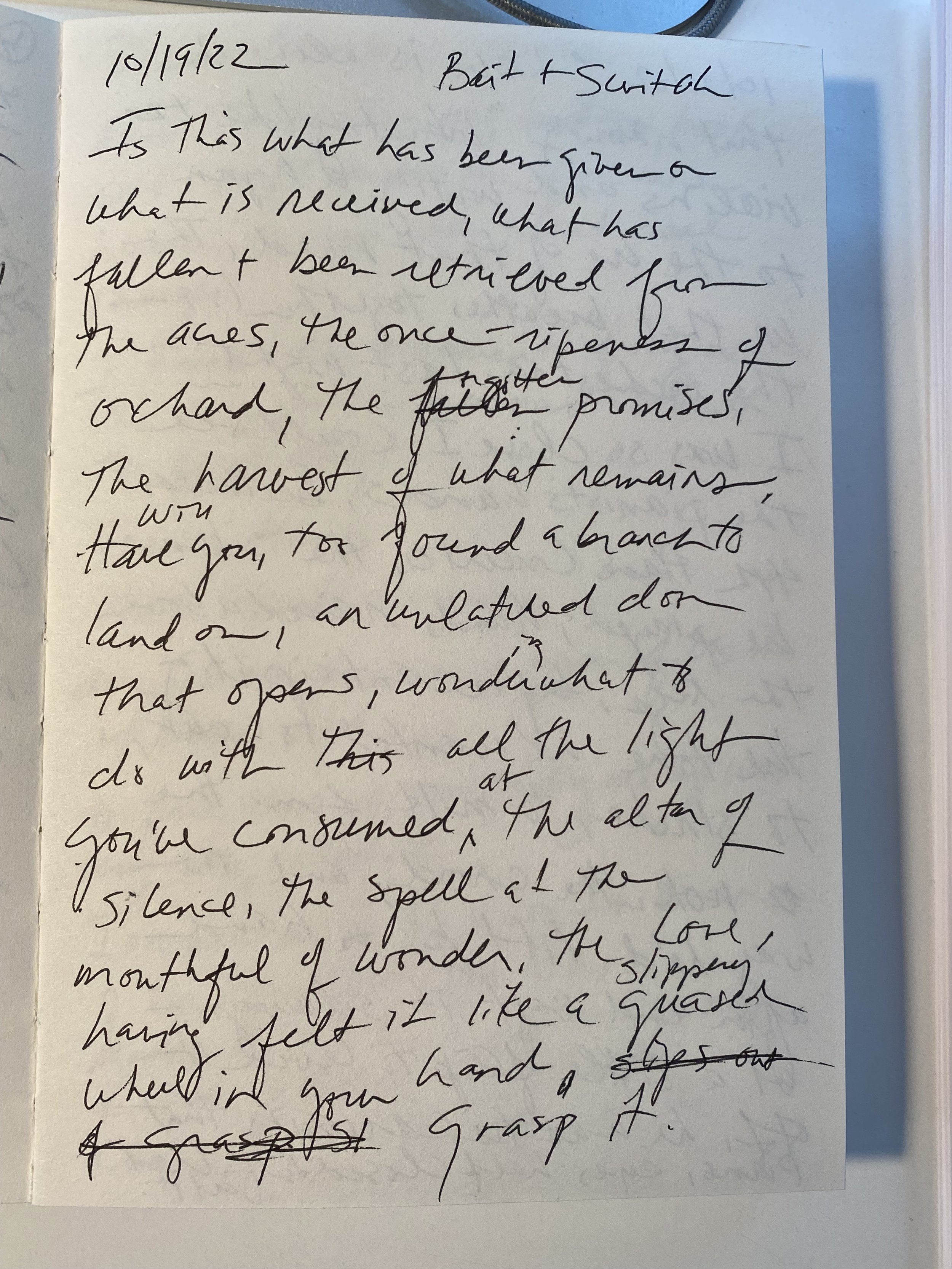

When I sat down to work on my poem again, these words came into my mind: “Is this what has been given, or what is received? What is fallen and retrieved from the acres. The once-ripeness of orchard. The harvest of what remains. Will you too find a branch to land on, an unlatched door that opens, wonder what to do with all the light you've consumed . . .” That just came out in a burst. I don't know if it was from ruminating on the image or what. So then I glued the phrases together. I had something like sixteen lines, and I felt like some of the writing wasn’t connected to anything. I've also been reading Diane Seuss's book frank: sonnets with my workshop, and we've all been writing sonnets. I wondered if I could make a sonnet and get rid of some of the lines that weren’t working. I also saw that the blocky shape of a sonnet would resonate with the mat shape of the apples, which was a solid rectangular block. The form of the poem could then enact the content of the image. So that was my process of cutting my draft down to fourteen lines.

Are there any other memories related to apples that you want to talk about?

Now that you mention it, my stepfather would eat an apple every night before he went to bed. He would stand at the kitchen counter, take a whole apple, slice it with a paring knife and eat it in sections. Sometimes he would give me a section, and it always tasted good. I also feel like apples are a treat. Apples are high FODMAP, and for months I wasn’t able to eat them. It wasn’t until this fall that I felt like I could eat them again. One of my favorite snacks as a teenager, and even into adulthood, is to core an apple and fill it with peanut butter. That's delicious. Those flavors -- the crunchy, viscous, meaty peanut butter with the sweet crispness of the apple. It's a really nice combination.

Another thing I found really beautiful about this piece is relating that life cycle of apples to love and life. Is there anything else related to that that you would like to talk about?

I often find that I really practice what Flannery O'Connor is supposed to have said: "How do I know what I mean until I see what I say?" With something as concrete as this image, and also as abstract in terms of subject matter, I think my poem was looking for a subject through language. Evoking what came up for me as I studied that image, and listening for the sounds of the words. It's about life, it's about death, even if I wasn't consciously thinking of those things. And love showed up – that was a really nice surprise. The words just come out, and I don't know where they come from. My mentor always said, "The poem knows more than you do."

Everyone has a different relationship with that process, and the unknowable nature of it. Do you feel like you struggle with it, or is it comfortable to allow things to come through like that?

I'm very comfortable with writing without knowing what I mean. I studied for years with Barbara Helfgott Hyett in her PoemWorks Workshop for Publishing Poets. She also invited poet friends to come to her house on Monday mornings and do free writes. We'd do nine free writes in a row, with prompts from an old set of the World Book of Knowledge. We'd thumb through those volumes, find phrases, write them on scraps of paper, and put them in a basket. We’d take turns pulling one phrase out for each round and we’d write for four minutes and nineteen seconds, and we had no idea what was going to happen. I still do those free writes on Monday mornings. Not every week, but a bunch of us are still meeting weekly. And I'm teaching now, this is my fifth year as the poet in residence at New Mission High School in Hyde Park. So I really carry that spirit into the classroom, and we begin every class with a free write. Often, even people who want to write poetry aren't comfortable just letting go and not thinking about what they're going to write before they write it. It's a gift to be able to do that without judging yourself every time, to hear that a word rhymes with another word, to write that word with the freedom to go off in that direction. And to see what shows up. I hope my students will learn to trust that process.

That's so cool that you have that practice of just opening that channel and allowing stuff to come through. It's like a muscle.

Right. And images are really effective for evoking that, to begin to describe what you see right in front of you. You don't have to search.

You mentioned that you often free write for four minutes and nineteen seconds. Why that specific amount of time?

I think it's somewhat arbitrary. It's what Barbara said was the right amount of time. It's long enough to say something. On very, very rare occasions, a whole poem will emerge from four minutes and nineteen seconds. It's enough time to get started with something substantive, but not so long that you're going to overdo it. It forces you to stop when you're still a little hungry.

I love it. I'm going to try it! Is there anything else related to this piece or your process that we haven't talked about yet?

A question that I'm thinking about these days is the use of pronouns. I love the way that Diane Seuss brings the reader so intimately into her poems. I see now that I began this poem in the first person. I tend to play around with whether to shift the pronoun to the second person you, which then becomes more intimate and inclusive, and where in the poem to do that. In this piece, I shifted midway through, which coincides with the turn. I think that's a semiconscious thing that I play with. I like that intimacy, and making the poem an experience for the reader, not just for the writer. I also like the idea of having questions in a poem. It can be overdone as well. A friend once said, "Don't ever ask a question you can answer," which is a good guideline. I've noticed that some poets have questions, but don't use question marks.

Have you noticed that question marks don't seem to be as popular as they were? I find that people often will text me questions without question marks, and it makes me really confused. Why is that? What happened?

Right. Are we just being lazy or is the question rhetorical, in which case it wouldn't have a question mark?

Maybe sometimes these questions are rhetorical, even if the person asking them doesn't intend them to be.

That's the beauty of poetry: you can ask questions that you don't have to answer. Just let them hang in the air. Some poems slam down and shut with a bang, and some are open-ended, leaving the answers and the questions for the reader to think about. I think poets are generally moving towards more open-ended poems that resonate in the reader's lap.

Do you usually end them open-ended, or do you lock them down?

My poems are more open-ended now. When I first began writing, I thought poems had to have a strong punchline, ending with a revelation or surprise. I think poems really benefit from a turn, but they don’t have to snap shut at the end.

Do you have any advice for another creative person approaching this project for the first time?

I really like the idea of just looking. Just begin by not thinking. Begin by describing the prompt. If something comes into your mind, then go for it, but if not just start by looking. What am I seeing, and how can I describe it? I wrote a poem based on a photo at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester. It was a gorgeous photo of ripe tomatoes on a window shelf, and the background was sepia-toned. And so I started writing about all the tomatoes, and looked up different types of tomatoes to get that language. I was describing the tomatoes for a long time, and it wasn't until much later that I realized there was a woman standing behind them. So that's how I ended it, “I see you, woman with the cup of still-warm coffee in your hand.” So I'd say to look closely, and maybe you'll surprise yourself with what you hadn’t noticed, and the poem will become the process of noticing.

Call Number: Y91VA | Y94PP.dreHa

Wendy Drexler is a recipient of a 2022 artist fellowship from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Her fourth collection, Notes from the Column of Memory, was published in September 2022 by Terrapin Books. She’s been the poet in residence at New Mission High School in Hyde Park, MA, since 2018, and is programming co-chair for the New England Poetry Club.