Response To Cherry Quionoa Truffles

Julia Skinner

“If you’re offered the inability to contextualize it, how do you approach that food?”

Interview by L. Valena

Can you tell me what you responded to?

I responded to the Cherry Quinoa Truffle recipe that I was sent.

What was your first reaction when you opened up that recipe?

It looked really good, but I was kind of confused by the quinoa in it. I was curious what that was going to do. I ended up really liking it, but I was wondering at first.

This was our first time passing on a recipe as a switch, which I felt confident doing, because it seems like you're a badass chef! What happened next?

I opened up the recipe, and since I had two weeks to do it, I decided to give myself a few days to kind of think about how I might want to respond, to inform me as I started cooking. I ended up having a bit more a time crunch than I thought I would, and just decided I would have to figure it out on the fly. I ran to the store, and got all the stuff, and started making it. It's not a recipe you can make super quickly, it's not days and days to make, but there are a lot of steps, and it requires a lot of mindfulness to do things like tempering chocolate. Using double boilers without burning all the stuff.

It's not a set it and forget it kind of recipe.

No, definitely not. So I started cooking it, and that mental presence that was required at a time when I was very rushed, and worried about how I was going to respond to this, greatly informed the response I ended up making.

Tell me about your response.

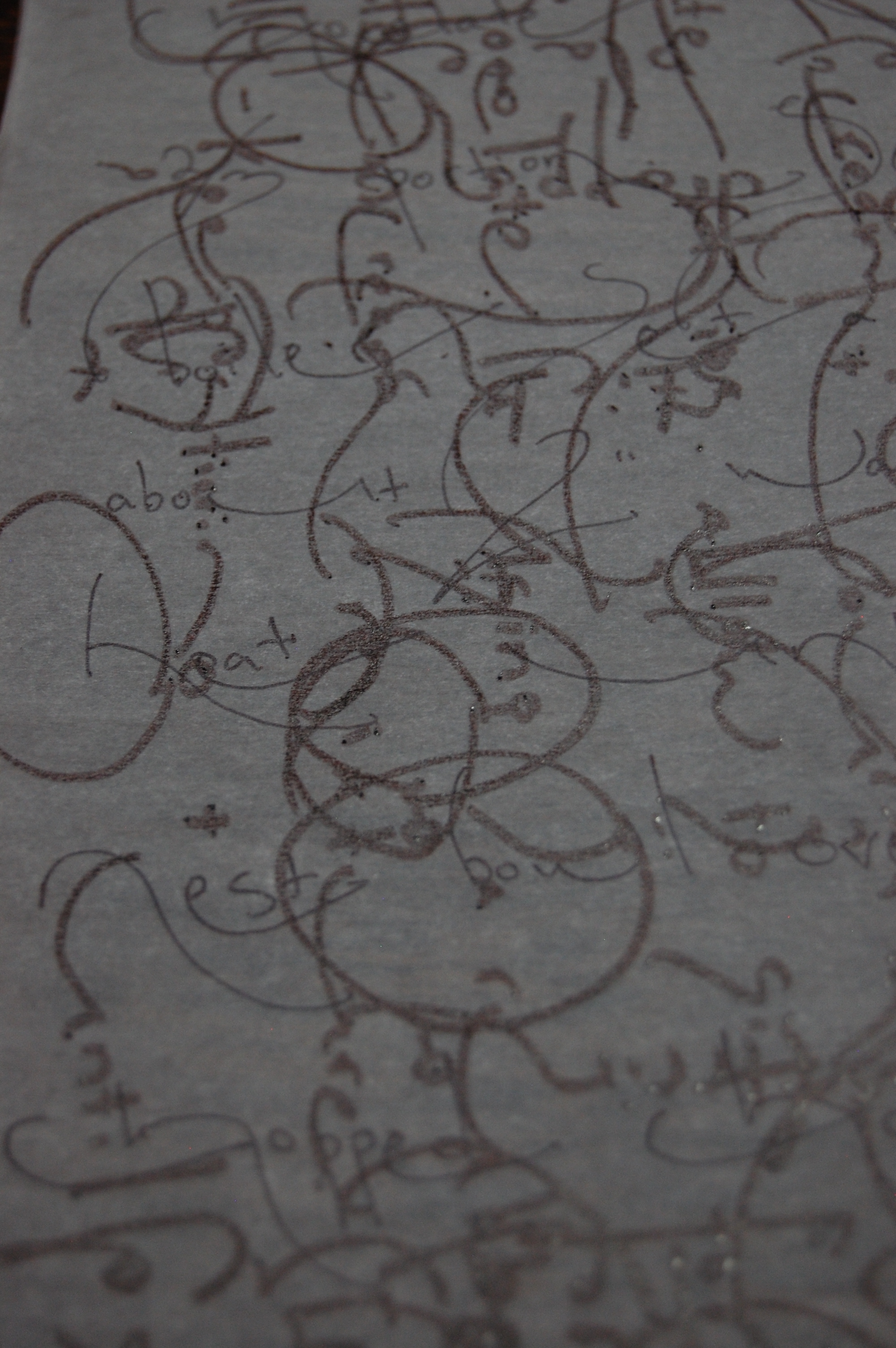

I initially was thinking of making a response recipe to this, maybe something that was a savory compliment. But I decided an art response would be a bit more interesting for conveying what I wanted to convey. So what I did was I used food-grade parchment paper, and did calligraphy on one set and did drawings on the other set, which represented different ingredients. So for example it's got cherries, so there are pictures of cherries, things like that. The calligraphy one is the recipe written in what is called a cane cursive, which is a calligraphic hand that can be really legible or really not, depending on how you do it. And I layered it to make it- it looked like there were words there, but they weren't really legible, so it decontextualized the recipe. I did that because I became curious about as I was making these truffles. I talked about quinoa being an unexpected ingredient. When you are expecting something in a food versus when you are, how can art be used to help provide that framing or remove that context? If I put a picture of cherries on there, you're going to expect that presumably this item that you're about to eat has something to do with cherries. And if it doesn't taste like cherries, you're going to be super confused.

Maybe even suspicious.

Right. What are you giving me right now?

This is lies!

I did that, and then the one with the written recipe was trying to offer the same raw information, but you can't actually read it. So if you're offered the inability to contextualize it, how do you approach that food? How does that change? I have this dream of at some point doing this and actually giving these out to a bunch of different people in different wrappers, and having them write down their thoughts or something.

Yeah, I love that idea- that would be so cool. Give them some blank paper and see if they write or draw?

Right. Ask how they respond to it, and tell them to just go to town.

So it sounds like the unexpected ingredient, and your immediate emotional response to seeing that ingredient, ended up being kind of a catalyst for the response.

Yeah, and I think I wasn't expecting that. There's lots of times when you look at a recipe and think oh, I didn't think that would be in there, okay. And you don't really think of it much more. But for some reason this time I really focused in on that.

I know you cook from historic recipes a lot, which is something I've done a bit myself. I think when you cook from historic recipes you become a little desensitized to weird combinations. You get a recipe for something that includes suet, raisins, and rye flour, and it's totally normal.

And it's funny, because I think if I would have seen suet, raisins, and rye flour, I would have thought to myself, makes total sense, because I'm just so used to working with early modern recipes and stuff.

Right! But this recipe was itself an artistic response, so it may not have quite as much cultural precedence.

But it still has a lot of it in there- it's a really cool recipe, I really enjoyed sitting with it.

Can you talk a little more about how this relates to the rest of your work?

I am the owner of a food history organization called Root, which is still in it's first year. It's a very young little organization. At this stage, there isn't much in the way of food history organizations our there, aside from professional organizations. It's very broad right now, basically I'm doing everything from modernizing recipes, so there's a weekly membership program where I share modernized recipes. I also do consulting- I'm actually assisting with a sci fi film right now.

What?! Can you talk about it?

I can talk a little bit about it. It's a post apocalyptic film, and it's set not so far in the distant future- say if the world ended maybe a hundred years from now. Part of what I enjoy about it is I'm using my background and thinking about the history of food. I also work as a professional fermenter, that's the kind of cheffing that I do. So doing all of this, and thinking about technologies around food, food is technology, and being able to map that forward. If we as a species didn't have the modern conveniences we have, what would we turn to? What would these technologies look like? How would we adapt artifacts we have now into less technologically advanced spaces?

That's so interesting! It's so cool that you're consulting with them- that's a very nuanced and detail-oriented version of post-apocalyptic thinking. That's pretty cool.

The other big thing I do is community work. Food is a very community-oriented thing. So part of what informed this response was that community mindset. I'd really like to just hand people this thing, and ask them to respond to it. Everything I do, I'm trying to bring more people to the table, I'm trying to get more people to think about all the ways they are connected to food.

Call Number: C10FD | C13VA.skiRe

Dr. Julia Skinner is a food historian, professional fermenter, academic, and mixed media artist living in Atlanta, GA. Her work focuses heavily on community and identity, and she tries to weave in community building and healing into all of her work as a chef, an artist, and beyond. You can find her food related work on social media @rootkitchens and the rest of her work at @bookishjulia